Perspectives on Japan’s Pleasure-Seeking Past: Discovering Ukiyo-e

Sometimes I turn into a cloud like smoke from tobacco I have lit, other times I turn into rain which makes a client linger a bit. - Santo Kyoden, poet

Tokaido gojusan tsui (1845-1846) by Ando Hiroshige. This depicts a wild scene from the comic graphic novel "Footing It Along the Tokaido Road" or "Shank's Mare" by Jippensha Ikku. ©Art Walters Museum

Introduction to the Floating World

Pleasure was serious business in 18th century Japan. It was so serious that even an expression was created to reflect its growing significance at the height of the Edo period (1615-1868). Ukiyo (“the floating world”) describes the hedonistic tastes and pleasure-seeking ambitions of the rising merchant class (chonin) in Edo (modern day Tokyo) and Kyoto. The Edo period saw the most vibrant manifestations of the extraordinary floating world of pleasure reflected not only in theatrical art forms, such as Kabuki, but also in visual art mediums like ukiyo-e. Ukiyo-e (浮世絵), commonly known as “pictures of the floating world,” are Japanese woodblock prints that have earned a coveted spot among the world’s most internationally recognized art forms. The words "ukiyo" and "e" literally mean, “the world of the common people” and “picture,” respectively. The former expression (“common people”) alludes to an emerging nouveau-riche that spent its wealth on Kabuki tickets and courtesans; the latter, in reference to lavish snapshots of life in Japan’s entertainment districts. Ukiyo-e’s emergence and growth reflects both the rapid rise of urban, merchant-class culture in 18th century Tokyo, as well as increasing urbanization in the major cities. These powerful social and economic forces fostered a lively popular culture focused on sensual pleasure and theatrical entertainment. Recurring themes in ukiyo-e include images of famous actors, geisha, sexually aware courtesans, as well as flora, fauna and well-known landscapes. Just as many of us loved to paper our walls with the likeness of our favorite movie stars, Edo Period collectors and theatre spectators collected images of their favorite Kabuki actors. Just as we purchase for loved ones postcards of cities and towns that we visit while on vacation, more and more citizens of Edo collected landscape ukiyo-e as they became wealthier and could take leisurely trips.

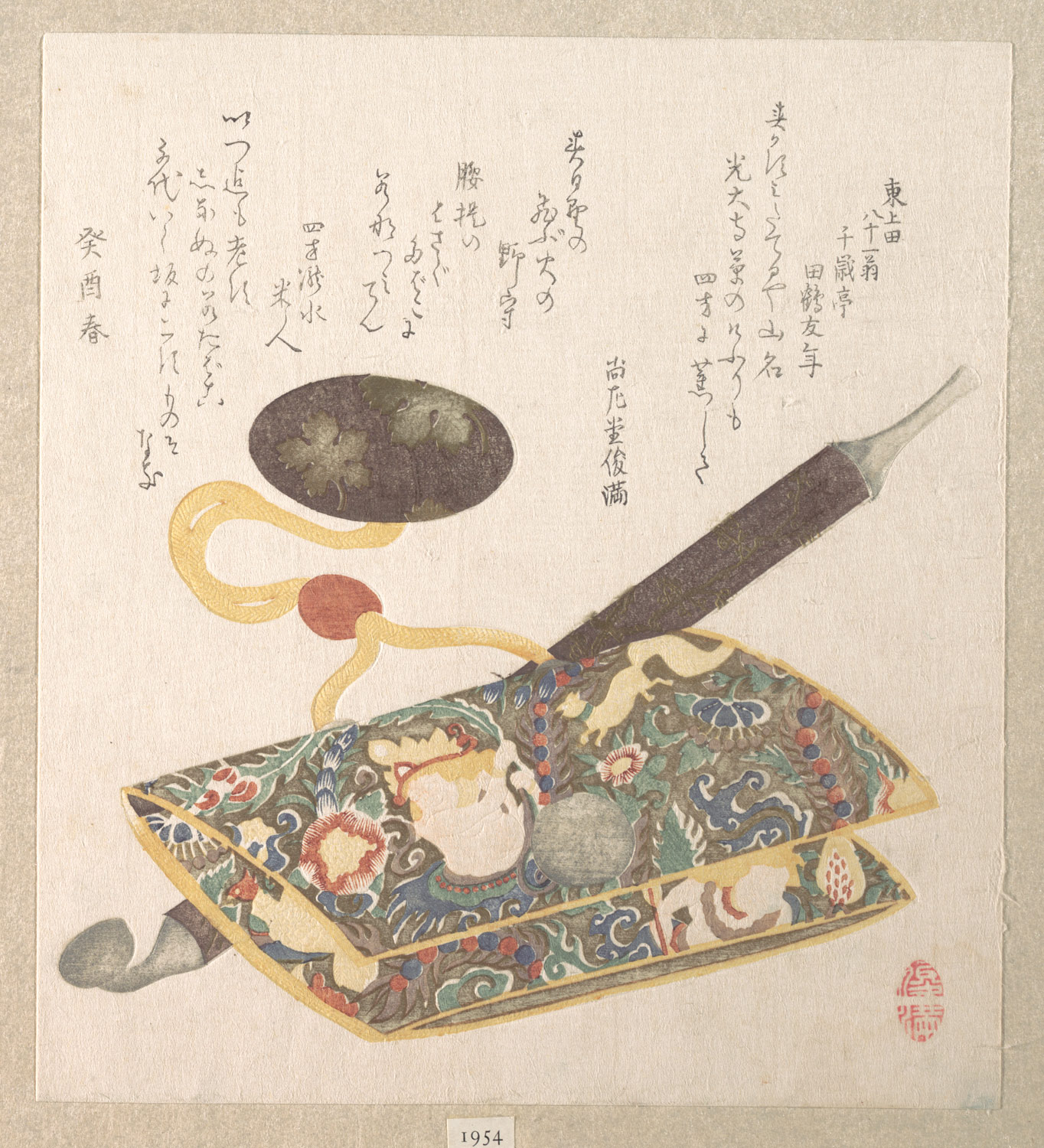

From the Spring Rain Collection (1810s) by Kubo Shunman. This represents the epitome of the highest quality of surimono ukiyo-e prints. ©Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Origins of Ukiyo-e

Ukiyo-e first appeared in the late 16th century. Early depictions showed examples of everyday life in the city of Kyoto, Japan’s former capital. Woodblock prints have existed in Japan since the 8th century. They were used primarily to disseminate religious texts, and until the 18th century remained a convenient method of reproducing written texts. However, in 1765, advances in printing techniques made it possible to produce single-sheet prints in a whole range of colors. Printmakers who had produced monochrome designs (sumizuri-e), later painting colors into prints by hand, gradually started using full polychrome painting to spectacular effect. The first polychrome prints, or nishiki-e, were actually calendars made for wealthy patrons in Edo, where it was the custom to exchange beautifully designed calendars (surimono) at the start of the New Year. The process of producing the prints requires three stages: painting and designing, carving, and finally coloring and pressing. Originally, ukiyo-e were not actually prints. Instead they were paintings made with sumi (black ink). Ukiyo-e artists, sometimes referred to as painters, were more like designers, and woodblock artists were generally painters who did not participate in making the prints that contributed to their designs. As designers, ukiyo-e artists sold their drawings to local publishers who in turn oversaw their printing. The most luxurious and elaborate woodblock printings often contained clever, but subtle visual and literary references that shrouded potentially taboo modern subjects. This appealed to a discerning and sophisticated urban audience, including the writers, artists and actors who were leading players in the floating world.

The Great Wave off Kanagawa from a Series of Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (1831-33) by Katsushika Hokusai. Known as one of the preeminent Japanese prints in the world, here the artist casts a traditional landscape theme in a bold and imaginative way.

From Wrapping Paper to Japonisme: Ukiyo-e’s Influence in the West

Ukiyo-e were immensely popular in the West, particularly in Europe during the 18th century, due to their affordability, portability and exoticism. At the height of ukiyo-e’s popularity in the 1830s, access to Japan was strictly controlled. It was only in 1859, due to pressure from America and other powers, that Japan began to open its ports and allow Japanese prints began to be exported abroad . . . in a manner of speaking. At first, ukiyo-e was absent from major Western art salons and major private collections. Rather shockingly, European painters noticed ukiyo-e prints being used as wrapping paper to ship goods from East to West. But Western artists quickly took notice of the prints, having been struck by the genre’s well-defined curves, bold use of color and audacious design. Ukiyo-e gained almost immediate popularity. Japanese woodblock prints were quickly discovered and celebrated by famed European and American Impressionist painters and Modernists such as Whistler, Van Gogh and Monet. Particularly notable is Hokusai’s “Great Wave” print which served as the inspiration for Debussy’s symphonic sketches of La Mer.

Queen Amidala with R2-D2, on ukiyo-e woodblock print (2015) ©makuake.com

Ukiyo-e Today

Once an affordable art form due to its ability to be efficiently mass produced during the Edo period, woodblock prints were originally sold in small local shops and on the street for no more than the cost of a bowl of miso ramen. However, things have changed substantially! Although demand for works by 18th century masters has fallen as of late, international collectors and local aficionados continue to crave iconic pieces of classical art from Japan’s Edo period. At the turn of the 21st century, a Hokusai or Hiroshige print could sell for over $1,000,000 USD. Whereas today, prices are more modest, with Toshusai Sharaku pieces recently selling for between approximately $600,000 and $300,000 USD. Ultimately ukiyo-e reflects Japan’s fantastic period of hedonism, mass consumption and a renewed appreciation for the natural world. Whether you choose to enjoy woodblock prints in their original form, in emoji-form or even in the form of a Star Wars motif, ukiyo-e has stood the test of time and remains one of Japan’s most loved and internationally recognized art forms.